14 June 2024

Naked Lunch

William S. Burroughs

Grove Press, 1959; 193pp. Restored text ©2001; 280pp

Caution alert: this review contains disparaging language and drug lingo based on the text of the book

The text I used includes Naked Lunch¹ (the novel) plus:

“Original Introductions and Additions by the Author”:

- Depositions: Testimony Concerning a Sickness (1960)

- Post Script…Wouldn’t You? (1960)

- Afterthoughts on a Deposition (1991)

- Letter from a Master Addict to Dangerous Drugs (1956)

“Burroughs Texts Annexed by the Editors”:

- Editors’ note

- Letter to Irving Rosenthal (1960)

- The Death of Mel the Waiter (undated)

- Outtakes (11 items)

According to Burroughs, “The title means exactly what the words say: NAKED Lunch—a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” (His upper case, from “Deposition,” p 199) — sort of a “reality sandwich.”

The book is composed of loosely connected vignettes, intended by Burroughs to be read in any order, following a junkie who takes on various aliases as he meanders around the world — though you’d be hard-pressed to know this without a Cliff’s Notes at your side.

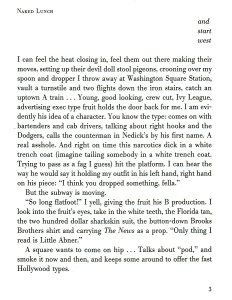

Oddly, although the novel is written in a sort of non-linear, magical realism / Joycean / free-form style, mostly unintelligible, there are short parenthetical notes (usually to explain a slang cultural term) in the text that are perfectly understandably phrased. Since the novel went through numerous revisions and edits over the course of 7 (?) years, it’s possible that WSB added these in later versions. They certainly seem out of place (because they’re grammatically understandable), though helpful. As with Salman Rushdie², it helps if the reader has a bit of familiarity with the culture or can decipher the slang in its context, like “fuzz” “flatfoot,” “pod” and the phrase “spoon and dropper” (presumably the spoon to cook cocaine and the eye-dropper used by addicts as a makeshift syringe). Considering that Burroughs identified as gay, there are a numerous disparaging homosexual terms (fruit, queen, fag, etc, presumably allowable for insiders, like Gertrude Stein also, to use. See, e.g. the 1st page, depicted below).

Basically, you’re getting first-hand info, advice and descriptions from someone who probably knows more about the nature of drugs, the drug experience, and treatments than anyone in the world as well as hiding from the fuzz. But, of course, it’s coming from a drug-addled writer on the lam.

In the additional texts for this edition, WSB writes in a very intelligible, almost clinical style. This leads me to wonder if he was purposely writing in a free-form Faulknerian stream of consciousness style or simply laying down the text of the novel during his continual 40-year drug-induced state.

- “The study of thinking machines teaches us more about the brain than we can learn by introspective methods. Western man is externalizing himself in the form of gadgets.” [Dr. Benway, a character in Naked Lunch, p22. Ironically, this could have been written by a commentator in 2024.]

- “If you wish to alter or annihilate a pyramid in a serial relation, you alter or remove the bottom number. If we wish to annihilate the junk pyramid, we must start with the bottom of the pyramid: the Addict in the Street, and stop tilting quixotically at the “higher ups” so called, all of whom are immediately replaceable. The addict in the street who must have junk to live is one irreplaceable factor in the junk equation. When there are no more addicts to buy junk there will be no more junk traffic. As long as junk need exists, someone will service it.” [“Deposition: Testimony Concerning a Sickness,” part of authors “Additions” to Naked Lunch, 202]. Burroughs goes on to say,” Addicts can be cured or quarantined…when this is done, junk pyramids of the world will collapse.”

[One doesn’t know how much credence to give WSB’s drug treatment claims (see below) but we have to concede that he’s probably tried them all]

In “Letter from a Master Addict to Dangerous Drugs” (addressed to a doctor, Aug 3, 1956) Burroughs gives a rather surprisingly comprehensive and academic-sounding list of major drugs of his time (223-229). The letter is actually a proposed article on the effects of various drugs he has used in the course of 10 “cures” (reprinted from The British Journal of Addiction, Vol 53, No. 2)

- Opiates (morphine, Demerol, methadone, et al)

- Cocaine

- “Speed ball” – shooting cocaine at one-minute intervals alternating with shots of heroine/cocaine

- Cannabis indica (hashish, marijuana)

- Barbiturates

- Benzedrine

- Peyote (mescaline)

- Banisteriopsis caapi (harmaline, banisterine, telepathine): Yagé or ayahuasca (“the most commonly used Indian names for a hallucinating narcotic that produces a profound derangement of the senses. Closely related to LSD6.”)

- Nutmeg [really?]

- Datura – scopolamine

- Morphine addiction

List of possible treatment drugs he has used—but not necessarily endorsed

- Reduction cures; Prolonged sleep; Anti-histamines; Apomorphine – best method of treating withdrawal that he has experienced: doesn’t eliminate withdrawal symptoms but reduces them to an endurable level; Cortisone; Thorazine; Reserpine; Tolserol; Barbiturates; Chloralhydrate and paraldehyde; Alcohol – absolutely contraindicated; Benzedrine; Cocaine – “goes double” re alcohol; Peyote, Banisteriopsis caapi

¹ not The Naked Lunch (though that may have been the original title)

² Rushdie’s (1988) The Satanic Verses is written in what is sometimes called “magical realism” — blurring the lines between fantasy and reality, a la Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel García Marquez. However, WSB’s style is more akin to a 1950s beatnik cafe poetry reading, like Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (one of his drug compadres) with disconnected phrases, hipster street allusions, drug, prostitute and police slang. In short, it’s not an easy read.

The text on the left is the opening of the book, exactly as published. The text on the right was taken somewhat randomly from p 49 (“hospital”). Click on items for better readability

Burroughs doing his ill-fated “William Tell” stunt

Burroughs doing his ill-fated “William Tell” stunt